Sam McGough & Montana Sapphires

Founded over a century ago by Sam McGough, grandfather of Andrea, McGough & Company has proudly upheld a rich legacy of offering exceptional gemstones of the highest quality, including Yogo sapphires. Yogo sapphires are rare, naturally vivid blue sapphires found exclusively in Yogo Gulch, Montana. These sapphires are known for their exceptional clarity and unique cornflower blue color.

The following article, written by David Federman for Modern Jeweler magazine, recounts the history of McGough & Company, Yogo sapphires, the sapphire mining companies, and the rise in popularity of Yogo sapphires.

*Gem Profile by Modern Jeweler, originally released monthly from April 1983 to May 1993. These popular columns explored the origin, history, and significance of various precious stones. Each profile acted as both an informative resource and a market guide. Learn more about Gem Profile here.

Yogo Sapphire: True Blue

Gem Profile

By David Federman, Contributing Editor

(Original published date unknown)

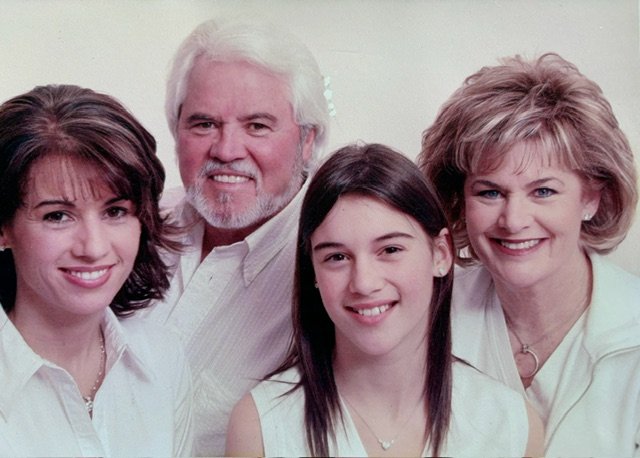

Welcome to Whitefish, Montana, a skier's paradise located on the edge of Glacier National Park. There a spacious souvenir shop with the suitably regional and rugged name of Tomahawk Trading Company sells more Montana sapphire than any other jewelry store in the world. Owner Sam McGough has made his store as much an advocacy, as a design, center for the state gem. As a result, 75 percent of the items sold there contain Montana sapphire from every producing locality.

McGough has been buying the largest sapphires coming from the state's famed Yogo Gulch mining area. And, for once, large means impressively noticeable to the naked eye—2 and even 3 carats plus. Those are giant sizes for America's most prestigious precious stone deposit. Most Yogos weigh considerably under 1/2 carat.

That Yogo is producing anything at all will probably come as a shock to readers who equate this legendary hard rock mining area with hard luck. Every attempt in the past several decades to launch and sustain a publicly-traded commercial mining venture at this sapphire motherlode has failed. The latest of them, Pacific Sapphire Co., seems to have thrown in the trowel last year.

Meanwhile, lost in the shuffle of worthless Montana sapphire mining shares is one Yogo venture that isn't giving investors the shaft. Purely private and very small, Vortex Mining has been bucking the long odds against survival at Yogo Gulch since 1989 and keeping hopes alive—if not high—for a comeback of what many consider America's finest gem.

Vortex Mining's survival strategy is as simple as it is successful: cut everything worth cutting that it mines and sell it loose or set through a gem and jewelry subsidiary, Yogo Creek Mining, located in Colson, a dot on the map so small it can't be found in Hammond's World Atlas. McGough just sold Yogo Creek's most buxom beauty for 2001, weighing 3.09 carats, for $47,000 total to a nouveau riche local as a gift for his wife. Last year, the same customer celebrated his entry into the good life by giving his honey Yogo Creek's largest stone for 2000. "He's become a collector – with Montana sapphires and Chevy Corvettes his pet passions," says salesperson Stacey Lamoureux.

Don't be surprised that Montana's rock classic can drive a man as wild as General Motor's sports car classic. Besides their homeland origin, Yogo sapphires enjoy a reputation for distinctive "cornflower" blue color as well as the rare distinction of being treatment-free. According to Robert Kane, president of Fine Gems International in Helena, Montana, the unique conditions and tremendous depth at which Yogo sapphires formed naturally endowed them with high transparency and true blue so they don't need the color and cosmetic boosts from heat treatment routinely given blue sapphires from Asia, Africa, and Australia.

The Tiffany Connection

Like every other Montana sapphire deposit, Yogo Gulch was discovered by gold prospectors who cared very little for the brightly colored pebbles they found as they panned for the yellow metal in 1879. Unlike those alluvial sapphires which had been transported far from their original birthplace, the first Yogo sapphires were found very near the original dike in which they formed roughly 50 million years ago, estimates author Stephen Voynick in his history of Yogo, The Great American Sapphire.

But that was only the first point of departure for the new corundums. Unlike other Montana sapphires which were usually light to medium shades of pink, purple, yellow, green, green-blue, and blue, the stones from Yogo were mostly medium to deep blue–rivaling the most sought-after shades of Burmese and Ceylonese goods.

No wonder gemologist George Frederick Kunz, long a Montana sapphire enthusiast, did a doubletake when in 1895 a cigar box full of Yogo stones was sent to him for evaluation at Tiffany's. Stunned by their beauty, Kunz sent the owner a check for $3,750, along with a letter that declared the sapphires to be "of unusual quality." Kunz was hardly alone in his amazement and admiration. In 1900, Yogo sapphires exhibited at the Universal Exposition in Paris won a silver medal in competition against stellar stones from Kashmir and Ceylon.

Those prizewinning stones were hand selected by the owners of the Yogo Gulch mine, then in its first full year of production under a British syndicate. Montana had joined South Africa for diamonds, Burma for rubies, and Ceylon for sapphires as part of the trifecta of world precious stone domination that England enjoyed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Under Charles T. Gadsden, who became mine supervisor in 1903, output of gem-quality sapphire from the New Mine Sapphire Syndicate increased steadily to 100,000 carats in 1910.

Ironically, competing operations such as the American Sapphire Company found the going too rough. All but the New Mine Syndicate eventually failed. As each of these ventures went bust, Gadsden persuaded his directors to buy them and then turned them into profitable operations. Only World War I stopped the syndicate's expansion. Afterward, it was all downhill from there as operation costs soared and production dwindled. In 1929, the Great Depression finally forced closure of the New Mine. No subsequent operation until Vortex Mining managed to survive long-term. Nevertheless, the dream of viable commercial mining at Yogo lives on. But judging from Vortex's mom-and-pop ways and means, only the lean and mean will make a go of Yogo.